Stephen Smith: Bubble Magnets.

Astronomers say that exploding bubbles of magnetic energy might have helped form galaxy clusters.

A little over fifty years ago, before space shuttles, before the Hubble Space Telescope, and before satellite technology, electricity in space was not considered. Because the first teams of space scientists were "steely eyed missile men" with backgrounds in aeronautics and chemical fuel reactions, when evidence for electric current flow around Earth was found it was called a "radiation belt."

Although Kristian Birkeland had conducted experiments almost fifty years before the first science package was launched into Earth orbit, electricity remained unfamiliar to researchers conditioned to think in terms of gravity and mass. They had no concept of charged particles generating filamentary structures that could interact and create energetic phenomena—Birkeland's terella research and his study of Earth's aurorae were forgotten.

That lack of familiarity continues today when moving charged particles from the Sun are called a “wind” instead of an electric current. Charged particles impinging on a planet or a moon are referred to as a “rain” instead of an electrical discharge. Ionized particles moving within a helical magnetic field are called "jets of hot gas" instead of field-aligned flows of electricity. When abrupt changes in the density and speed of charged particles are observed, those changes are called a “shock wave” instead of a double layer. Birkeland continues to fret from beyond the pale.

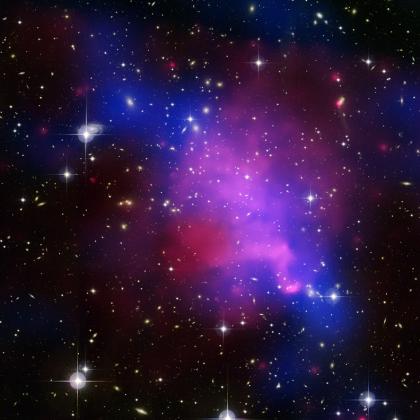

Magnetic fields in space can be detected more easily than electric currents, so modern astronomers think that the fields are fragments left over from the Big Bang. They write a blank check based on that conclusion to explain how the primordial structures that make up the universe were formed. An analysis of data from the Chandra X-ray Observatory seems to indicate that "bubbles" over 60,000 light years in diameter are slowly percolating out of galaxy clusters. Within this cosmic fizz are supposed to be intense magnetic fields that are released when the bubbles burst. Research teams speculate that the fields detected in remote galaxy clusters are caused by the bursting bubbles.

Galaxy clusters are thought to be made of individual galaxies embedded in hot gases and dark matter, so astronomers were surprised to find the bubbles, or cavities, within the overall x-ray emissions detected by Chandra. Inside most of the cavities are bright radio sources that could be caused by the explosion of highly energetic particles, but the cause of the explosions and the source of the particles is not known.

Even so, according to Brian McNamara from Ohio University: "We've known for the past 15 to 20 years that magnetic fields exist [in galaxy clusters], but we didn't understand how they got there. This could be a viable mechanism."

The fact that moving charges constitute an electric current and that those currents generate magnetic fields has been known since the days of Michael Faraday. However, since "perception is reality," as the saying goes, a lack of knowledge means a lack of vision. As previously stated, charged particles in motion constitute an electric current and that current is wrapped in a magnetic field. As more charged particles accelerate in the same direction the magnetic field gets stronger. That is a familiar idea to electrical engineers, but when astronomers find magnetism in space they are mystified. They resort to ironic ideas about galaxy-wide voids with magnetic fields frozen inside them.

Another fact that is not considered when attempts are made to explain structure in the universe (or smaller-scale planetary examples) is that for charged particles to move, they must move in a circuit. Hannes Alfvén, the father of plasma cosmology, identified several interacting circuits in the Earth's magnetosphere. One of those circuits forms the polar aurorae due to electric current effects linking the Sun with our planet's charged environment.

On the largest scale of all, the universe, larger energetic events are not explained by reference to local conditions. The effects of an entire circuit—which may encompass clusters of galaxies—must be considered. For this reason, while the consensus scientific worldview only permits isolated galactic "islands" in space, the Electric Universe hypothesis emphasizes connectivity with a vast network of electrically active "transmission lines." That spatial wiring is composed of Birkeland currents.

Loops and filaments suddenly expand and explode, throwing off massive bubbles of plasma that can accelerate to near light-speed. Jets from opposite poles of a galaxy end in energetic clouds emitting copious radio and x-ray frequencies. These are facts based in plasma science and not the traditional theories of gas kinetics, gravity, or particle physics. Astrophysicists see magnetic fields, but they do not perceive the underlying electricity, so they are at a loss to explain them.

Plasma behaves in unfamiliar ways. Its similarities to hot gas are overshadowed by its differences. It is habitual perception that makes it difficult to see plasma as something different. By breaking free from a priori assumptions, the unfamiliar behavior of plasma will become familiar and astronomers will perceive a new universe.

4 comments:

All very fascinating. I wonder to what degree the plasma is affected by gravity, and vice versa. I've got much learning to do regarding these matters. Are there any observations of this plasma in between the asteroids and around the asteroid belts?

....or, I would guess the asteroid belt is about an equipotential.

F = G x m^1m^2/r^2

As far as I can tell gravitation is a myth so it has no affect on plasma or anything else in the universe.

I'd like to point out that those are subscripts instead of exponents on the masses for the gravitational force equations, but the radius still is an exponent....

Hmmmm, anyhow, plasma has a rest mass, or else it would be experimentally possible to accelerate plasma to light velocities like photons. Of course, the electrical forces between elementary particles has been determined to be on the order of 10^40 times stronger than the gravitational forces between elementary particles which thereby makes gravitation neglidgeable on the quantum scale of things.

Electrical Cosmos, of course, is not about comparing the relative strengths of forces between elementary particles, but rather about determining the nature of electricity in the Cosmos. For that, we must dig up evidence of voltage potentials between objects in gravitational orbits or forces and currents between charged objects in motion which you are more well informed than I.

That being said, I can blindly guess at what the electrical nature of the Cosmos looks like, or I can get some actual evidence and imagery of the situation in order to make a better assessment of what things actually are occuring in astronomy.

Post a Comment