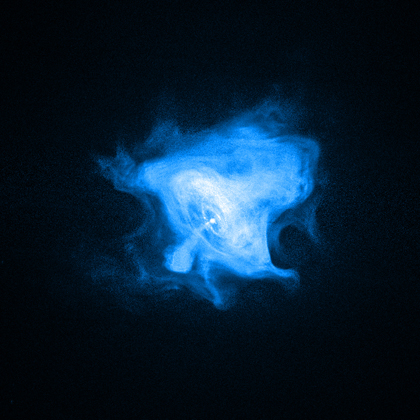

X-Ray (electromagnetic radiation emitted by electrons) image of the Crab Nebula, NASA Chandra X-Ray Telescope

Credit: NASA/CXC/SAO/F.Seward et al

Mel Acheson: The Consensus and the Crab.

Gravity is a weak force, and it can generate only a dribble of energy. Yet throughout the universe we see floods of energy.

The consensus of opinion among astronomers is that the energies of the universe can only come from gravitational mechanisms. Because the force of gravity, and therefore its energy, is directly related to mass, the floods of energy require enormities of mass.

Because the consensus opinion holds that magnitude of mass is equivalent to amount of matter, many of the floods of energy require more matter than can fit into the observed sizes of their sources. Consensus opinion takes recourse in boosting densities: by ignoring all that is known empirically and much that is known theoretically about the compression of matter, the consensus opinion can believe that however much matter is needed can be crammed into the available volume.

The coincidence of such super-densities with the requirements for gravitational production of observed energies is accepted as prima facie proof that the consensus opinion is, in fact, a fact, despite the circular reasoning.

This is the fact that makes the central star in the Crab Nebula’s inner x-ray structure (above image) a pulsar. The press release for this new image states matter-of-factly: “The nebula is powered by a rapidly rotating, highly magnetized neutron star, or pulsar (white dot near the center). The combination of rapid rotating [sic] and strong magnetic field generates an intense electromagnetic field that creates jets of matter and antimatter moving away from the north and south poles of the pulsar, and an intense wind flowing out in the equatorial direction.”

A neutron star has so much matter squeezed into it that the electrons have been squeezed into the nucleus to combine with the protons there and form neutrons. The uncharged neutrons are then packed together, as congested as commuters at rush hour. The pulsations of the pulsar are attributed to a hot spot on its surface that sends a flash of radiation with each rotation of the star. Its operation is analogous to a lighthouse light, back when such lights were mechanically rotating devices, before they were converted to electrically pulsed lamps.

The Crab Nebula’s pulsar pulses 30 times a second. This would mean that the star rotates 30 times a second. This would mean that the centrifugal force is stronger than the star’s gravity … which would mean that the star tore itself apart a long time ago, except that consensus opinion crammed in additional matter to bump up the mass sufficiently to increase the gravitational force enough to hold it together.

Of course, another possibility, one not considered by consensus opinion, is that, as with modern lighthouses, electrical oscillations make the pulsar blink. Super-dense matter and super-fast rotation aren’t needed. The x-ray structure—the jets and rings and sharp boundaries of the diocotron instability around the periphery—are common characteristics of plasma discharges … as is the strong magnetic field, the origin of which consensus opinion neglects to explain. Externally driven electrical circuits provide a unified and coherent explanation that is consistent with electromagnetic theory and laboratory investigations. It’s an explanation that doesn’t require exceptions, circular reasoning, or a consensus of opinion.